World Pieces

On a culture of accelerating fragmentation

A couple months ago, I searched for my band Sick Day on Spotify. I do this periodically to see what our page might look like to someone browsing the app. As opposed as I am to big tech’s strengthening chokehold on artists, I am also vain. I check my virtual presence like someone checking her appearance in a public bathroom’s mirror - timidly, obsessively, and a little too frequently.

Perusing the cold metrics attached to my soul’s work, I feel a mixture of hollow accomplishment (wow, 10k listens on Overexposure) and aching inadequacy (only 535 listeners after 6 years of effort), familiar in the age of disassociated “likes” and faceless followers.

This time, something looked different on my Spotify page. Where once the “Fans Also Like” section was populated with friends from the local music scene - Chaepter, Liska, Spliff - it was now a smattering of unfamiliar faces. These bands, with their quirky names, lo-fi profile pictures, and modest numbers of listeners, resembled my beloved Chicago collaborators. They were clearly local to somewhere - just not to here.

The slightly jarring experience of seeing my re-arranged Spotify page echoes Kyle Chakya’s reflections in his essay The Digital Death of Collecting. In it, he writes

I opened the Spotify app on my laptop a few weeks ago and found that everything I had saved was in disarray. The albums weren’t where I thought they were. I couldn’t flip through them with my usual clicks, the kind of subconscious muscle memory that builds up when you use a piece of software every day, like your thumb going directly to the Instagram app button on your phone screen. Spotify had updated its interface and suddenly I was lost. I couldn’t put on the jazz record by Yusef Lateef that I play every morning when I start writing and I couldn’t figure out where to find the songs I had saved by pressing the heart-shaped like button. The sudden lack of spatial logic was like a form of aphasia, as if someone had moved around all the furniture in my living room and I was still trying to navigate it as I always had. Spotify’s new “Your Library” tab, which implied everything I was looking for, opened up a window of automatically generated playlists that I didn’t recognize. The next tab over offered podcasts, which I never listened to on the app. Nothing made sense.

In the digital era, when everything seems to be a single click away, it’s easy to forget that we have long had physical relationships with the pieces of culture we consume. We store books on bookshelves, mount art on our living-room walls, and keep stacks of vinyl records. When we want to experience something, we seek it out, finding a book by its spine, pulling an album from its case, or opening an app. The way we interact with something — where we store it — also changes the way we consume it, as Spotify’s update made me realize. Where we store something can even outweigh the way we consume it.

…

Even if the change in the interface was minor — requiring an extra click to get to my playlists or moving the link to my saved albums — it’s a reminder that I don’t actually own any of what I’m listening to. I’m just paying for access month by month with my subscription fee to the streaming service. My relationship to music is ultimately dictated by the Spotify platform, both what I can listen to and how I listen to it. Unlike [Walter] Benjamin, I can’t pack up my collection and take it with me. My cultural aspirations are at the mercy of a corporation in Sweden: If Spotify clashes with a particular record label or decides a song format is unsuitable, I won’t be able to access it anymore through the channel I use most often, and I might very well just stop listening to it.

For musicians like me and listeners like Kyle Chakya, these seemingly small interface tweaks have a profoundly unsettling effect. And while this phenomenon may sound minor in the face of our society’s current problems, Spotify’s eerie digital re-shuffling exemplifies the greater cultural fragmentation of life in 2025.

More than ever, our lives are characterized by a deeply fragmented reality. The endless Facebook feed of 2006 feels quaint - it made us hate our friends, but at least we knew those people. Fast forward to 2025 and we have been mentally, emotionally, and spiritually gutted by a sickly smooth, vacant, and omnipresent Web 2.0. People barely socialize in-person anymore. We are hijacked into hundreds of passive parasocial relationships and paralyzed by a glossy awareness of dozens of disparate social and environmental catastrophes that galvanize us into fight-or-flight, and not much more. TV’s most riveting show is Severance, in which workers’ brains are literally split so that their work self is not conscious of their outside self. Trump is president again, and as he rips families apart and throws minorities’ accomplishments down the memory hole, we now gaze at him with the disassociated nausea of watching a bridge fall on TikTok.

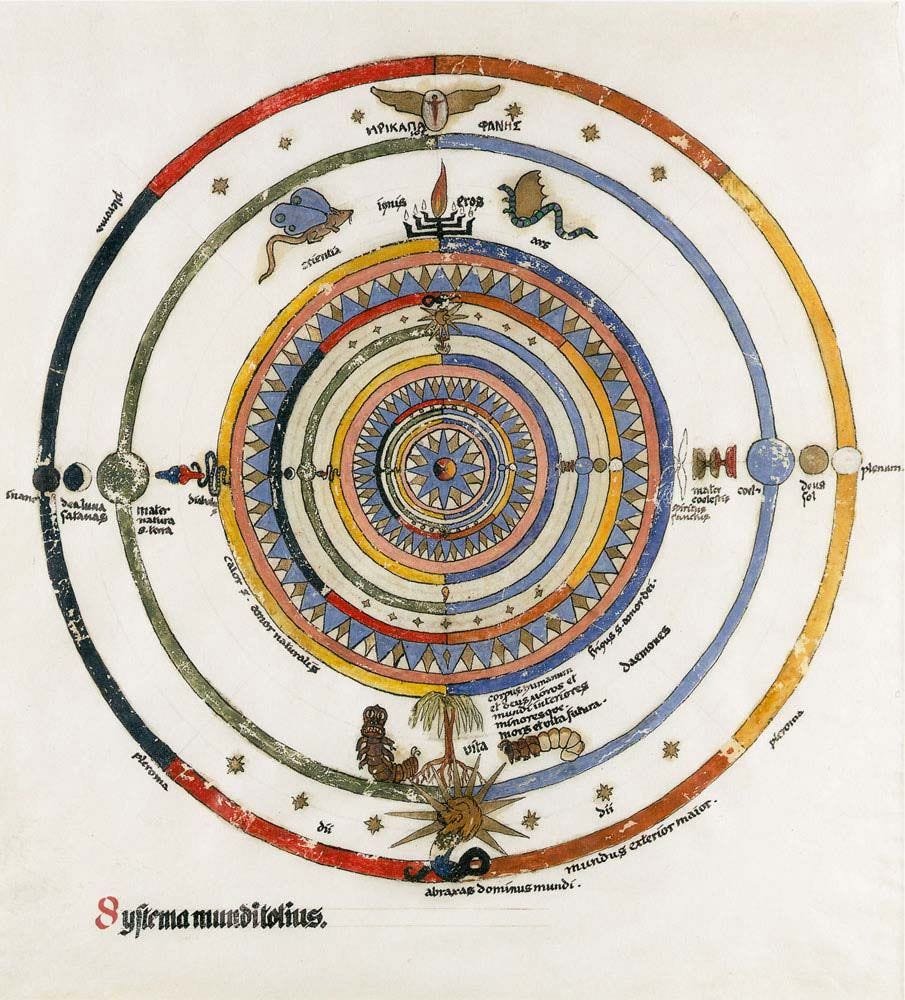

As I write this blog post, the symbol of the mandala comes to mind. In Hindu and Buddhist Tantrism, mandalas are painstakingly created and subsequently destroyed. Viewed by Carl Jung as symbols of psychological and spiritual health, integration, and wholeness, mandalas represent a world that intuitively makes sense - the opposite of our current culture of fragmentation. The mandala is fleeting like an Instagram story, but it is also sacred, reminding us of the importance of our time on earth and of our place in the cosmos.

Culture can only get so fragmented before people start to yearn for wholeness, connection, and a revitalized sense of the sacred. Maybe that’s wishful thinking on my part, and we’ll all end up so immersed in our phones and Fourth Walls (a la Wall-E and Fahrenheit 451) that we never talk to anyone but Chat-GPT again.

But in the Chicago music scene, I’ve seen evidence of a tipping point. People are meeting to chat IRL, air grievances, and dream about new ways of doing things.

This essay ended up a bit fragmented - apropos to its subject matter. To tie things up, I’d like to share a few links:

A link to donate to the Chicago Reader, a vital voice in the arts community

A link to donate to scene photographer Victoria Marie’s fundraiser for her medical bills

A link to tickets for Sick Day’s next show on February 4 :)

best regards,

Olivia

Sick Day